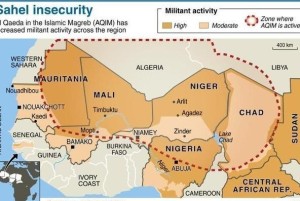

Mali extended a state of emergency by six months, from May until 31st October, as the west African nation battles a jihadist insurgency. MPs meeting in Bamako “voted unanimously” to extend the state of emergency. The measure has been renewed several times since jihadists stormed the Radisson Blu hotel in Bamako in November 2015, killing 20 people in an attack later claimed by al-Qaeda’s regional branch (Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb – AQIM).

The state of emergency decree hands extra powers to security forces and restricts public gatherings, though the country’s troubled north has witnessed a spate of jihadist strikes despite the emergency. In April, armed men killed five soldiers and injured 10 others in an attack on an army post in the tense Timbuktu region.

The last time the government extended the measure, it said the “security situation in Mali and in the sub-region is still characterised by the continued threat of terrorism and serious attacks on people and their belongings.”

In late April, French soldiers killed or captured around 20 jihadists in the area where a French soldier had been killed on April 5, the French chief of staff said on Sunday.

Troops from Operation Barkhane, the French counterterror operation whose mission is to target jihadist groups operating in the Sahel region south of the Sahara Desert, launched the operation south-west of the city of Gao.

Operation Barkhane, established in Mali in 2014, is comprised of 4,000 soldiers who are deployed across five countries – Mauritania, Mali, Niger, Chad and Burkina Faso, while in Niger, it operates four Mirage 2000 fighter jets and five Reaper drones for gathering intelligence.

“Since Saturday (29th April), the Barkhane force has been engaged in an operation which led to the neutralisation of nearly 20 jihadists in the forest of Foulsare near the border between Mali and Burkina Faso” announced French military spokesman Colonel Patrik Steiger

French Mirage fighter jets also bombed several arms depots in the forest, a sanctuary for armed terrorist groups.

Mali’s north fell under the control of jihadist groups linked to Al-Qaeda in 2012 when they hijacked an ethnic Tuareg-led rebel uprising. The Islamists were largely ousted by the French-led military operation in January 2013, but jihadists continue to roam the country’s north and centre, mounting attacks on civilians and the army, as well as French and UN forces still stationed there.

Earlier in April, French and Malian armed forces killed at least a dozen Islamic extremists who had attacked an army camp in northern Mali killing at least four soldiers. The attack on the army camp located around 120km east of Timbuktu also destroyed a half-dozen vehicles. French air assets, alerted by Mali’s army, responded as the assailants fled in two pick-ups.

The recently formed extremist group Nusrat al-Islam wal Muslimeen (Group to support Islam and Muslims – GSIM) claimed responsibility for an attack on Malian forces in Tagharost, about 150km south of Timbuktu. The extremist group said it had staged the attack, storming military barracks and taking vehicles. Ansar Dine, Al-Mourabitoun and al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) in March declared they had merged into Nusrat al-Islam wal Muslimeen. The 3 Malian jihadist groups with long standing links to Al-Qaeda recently joined forces to create the GSIM under the leadership of Iyad Ag Ghaly of Islamist organisation Ansar Dine. Ansar Dine had been involved in the initial onslaught that saw northern Mali fall out of government control for nearly a year from early 2012.

At the same time, a United Nations peacekeeping mission vehicle was escorting a logistics convoy when it hit a land mine about 30km south of Tessalit in the Kidal region, the UN mission said, wounding two peacekeepers and one civilian.

Though the French-led intervention drove Islamic extremists from strongholds in northern Mali in 2013, attacks from the jihadist groups continue. The area is also seen by regional governments battling the jihadist threat as a launchpad for attacks against the countries in the region.

Chad closed its border with Libya in January 2017, and declared the frontier region a military zone amid a “potentially serious threat of terrorist infiltration” Chadian Prime Minister Albert Pahimi Padacke said.

That move came just weeks after the African Union’s security chief warned that thousands of Islamic State (IS) fighters ousted from Libya by a four-month US bombing campaign could be planning a move into sub-Saharan Africa.

The Chadian Prime Minister said that troops had been sent to the Chad-Libya border region. “Some isolated groups have converged towards the south of Libya on the northern border of our country which is potentially exposed to a serious threat of terrorist infiltration,” he said in a message broadcast on state television and radio.

“Given the threats to the integrity of our nation, the government decided to close the land border with Libya and also to declare the region a military zone. By these two measures the government intends to deal with any eventuality likely to disturb the tranquility of our populations in these regions and to threaten peace within our borders.”

In December 2016, Smail Chergui, the AU’s security commissioner, had addressed AU member states on the threat to Africa from the Islamic State in Algeria. He warned that 2,000 to 2,500 IS fighters were regrouping after devastating U.S. airstrikes on their bases in the Libyan city of Sirte with a view to relocating to the troubled regions of the Sahel, the Horn of Africa and the Great Lakes.

Chergui said some IS fighters were of African origin and were already present in Yemen and Somalia. “Our priority is to be able to gather information and intelligence about them, share with our partners, then develop a concrete regional and international cooperation to curb the imminent terrorism danger”.

Though regionally Chad is seen as a repressive regime, presided over by Idriss Déby Itno for the past 26 years, it has become a key player in the regional military force set up to tackle Boko Haram, based in neighbouring Nigeria, but which has also launched attacks into Chad and Cameroon.

Though regionally Chad is seen as a repressive regime, presided over by Idriss Déby Itno for the past 26 years, it has become a key player in the regional military force set up to tackle Boko Haram, based in neighbouring Nigeria, but which has also launched attacks into Chad and Cameroon.

Boko Haram declared its allegiance to IS some years ago and in late 2015 a breakaway faction of al-Shabaab in Somalia followed suit. West Africa is also plagued by several al-Qaeda affiliates, one of which has attacked hotels and resorts in Burkina Faso, Mali and Ivory Coast in the past 12 months.

The growing regional terror threat has also prompted the United States to significantly scale up its military presence on the continent. Official figures released earlier this year revealed that Africa has seen the biggest growth of U.S. special forces operatives overseas than anywhere else internationally, with troop numbers increasing from 1 percent in 2006 to 17 percent in 2016.

However, some reports on the Libyan border closure hinted at an ulterior motive by the Chadian government, when a military base belonging to a rebel group that in 2008 had marched on N’Djamena to overthrow Déby was bombarded by regime forces in late December.

The timing of the Chadian announcement has also been questioned, as ISIS was routed from Sirte, 450kms east of Tripoli, in December 2016 after 8 months of heavy fighting, with Libyan forces (mainly drawn from the Misrata Brigades) supported by massive US air assets (an estimated 470 airstrikes reportedly took place between August and December 2016), and as early as July there had been a tactical withdrawal of IS fighters from Sirte, so the Chadian decision to close the border appears to have come late.

The threat of IS fighters leaving Libya is certainly real, because there are well established IS affiliates in Tunisia, Egypt, Algeria and Niger that have not been as active, and it appears that the Chadian concern is of IS combatants infiltrating across the borders into Libya’s neighbours to strengthen and prop up existing groups with reasonably well trained and battle hardened militants operating across the Maghreb

The Tibesti desert border regions are sparsely populated but are used for dealing in contraband by those living on both sides of the border, mainly the ethnic Tubu people, and Libya itself has been mired in chaos since the 2011 downfall of longtime dictator Muammar Gaddafi, with a variety of disparate militias still vying for control of the country.

Chad is seen as a key ally of the West in its fight against jihadists in Africa. President Idriss Deby Itno is supported by France and the United States, who both need the cooperation of the Chadian military in the region. The country is also part of the regional alliance fighting Boko Haram Islamists who have spread their insurgency from northern Nigeria to the border regions of neighbouring Chad, Niger and Cameroon.

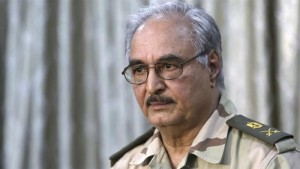

In Libya itself, Russia has been seeking an end to the arms embargo against Libya and could supply weapons to Field Marshal Khalifa Haftar, whose forces support a rival administration to the Tripoli-based, UN-backed Government of National Accord (GNA). Asked whether he had been promised arms during his recent visit to Russia, General Haftar said Moscow had told him weapons “can arrive only once the UN embargo ends. Putin will undertake to revoke it”

Haftar, the controversial head of the so-called Libyan National Army, supports a parallel authority, based in eastern Libya near the border with Egypt, that now controls much of the country’s oil production. The bitter divisions in Libya are matched by those among the international powers pushing for democracy in the conflict-torn country, where Western supporters of the GNA have prioritised the fight against Islamic State jihadists while simultaneously trying to impose controls on the migration flows from Libya towards Europe.

Haftar, the controversial head of the so-called Libyan National Army, supports a parallel authority, based in eastern Libya near the border with Egypt, that now controls much of the country’s oil production. The bitter divisions in Libya are matched by those among the international powers pushing for democracy in the conflict-torn country, where Western supporters of the GNA have prioritised the fight against Islamic State jihadists while simultaneously trying to impose controls on the migration flows from Libya towards Europe.

But another international group, including Egypt, the United Arab Emirates and Russia, see Haftar’s forces as a buffer against the perceived Islamism of the GNA

Haftar said he was open to dialogue with GNA head Fayez Serraj in principle, but it was impossible to talk politics under current conditions in Libya. “We are at war, security issues take precedence. It’s not an opportune time for politics. We need to fight to save the country from Islamic extremists. I began talks with Serraj two and half years ago. Without any concrete results. Once the extremists have been beaten we can start talking about democracy and elections again. But not now” he declared

Haftar denied media reports of an upcoming meeting with Serraj, saying the last time they had spoken directly was in January 2016. But he admitted “I have nothing personally against Serraj. He is not the problem, it’s those around him. If he really wants to fight to make peace in the country, he should take up arms and join our ranks. He is always welcome.”

Haftar complained of countries providing support to the GNA but not to the rival Tobruk-based House of Representatives (HOR), where he is located, saying “we expect help from everyone to fight IS. We would be happy to cooperate with Great Britain, France or Germany. Italy too”.

The internationally backed GNA was formed in March 2016, intended to replace two rival administrations, one in Tripoli and one in the east of the country at Tobruk. It is also the centrepiece of Western hopes to stem an upsurge of jihadism in Libya and halt people trafficking across the Mediterranean that has started to create social chaos in Western Europe

Despite the international support, the GNA has failed to assert its authority fully over the whole country, where Prime minister-designate Fayez al-Serraj has not yet been able to secure a vote of confidence in the Libyan parliament based in Tobruk in the east .

Leave a Reply