Local elections in Mali on Sunday 20th November, the first elections in Mali since 2013, to elect some 12,000 councillors, were marked by low voter turnout, protests and incidents of violence, however the polls, first scheduled for 2 years ago and delayed several times due to security and political concerns, were seen in Mali as at last a small step forward. The success of the elections was considered a key element to a peace deal which includes the creation of interim administrations in the country.

The elections were boycotted by several opposition parties and some armed groups, including the Tuareg rebel group (formerly known as the Coordination of Azawad Movements – CMA). In Kidal, the bastion of the Tuareg armed rebel group, residents boycotted voting and several hundred people demonstrated there against the holding of the elections. Tuareg separatists held signs saying that the elections should not be held before the appointment of “intermediary authorities”.

They reportedly burned Malian and United Nations flags.

Mali’s President Ibrahim Boubacar Keita said after casting his vote, “We have already delayed these elections four times so that they can be inclusive and four times is enough.”

Mali’s President Ibrahim Boubacar Keita said after casting his vote, “We have already delayed these elections four times so that they can be inclusive and four times is enough.”

The elections however did not proceed entirely peacefully, with six people killed on polling day, including five Malian soldiers who were ambushed while transporting ballot boxes in the north of the country.

In a statement ahead of the elections, UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon had asked the Malian government to “pursue a constructive dialogue with all stakeholders to defuse tensions that may arise before and after the poll.”

He also called for a peaceful vote in areas “where political and security conditions allow.”

In the southwest of Mali, presumed jihadists stole vehicles and killed a civilian. According to a local official, “they arrived early Monday in Dilli. They attacked a council building. The jihadists took off with two ambulances and a vehicle, after which they killed a civilian and made off for the Mauritanian border”.

It is alleged the jihadists were looking for ballot boxes in the building while counting took place.

Participation in the polls was reported to be low, with Bamako reporting 25 per cent turnout in three of the city’s six districts. Turnout was highest in the southern city of Sikasso where some 50 per cent of eligible voters went to the polls.

Participation in the polls was reported to be low, with Bamako reporting 25 per cent turnout in three of the city’s six districts. Turnout was highest in the southern city of Sikasso where some 50 per cent of eligible voters went to the polls.

Moussa Ag Assarid, an activist with the National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad (MNLA), described the polls as a “farce”. “It was a big aberration to support those in power in Mali at the moment, who do their level best to deny the existence of Azawad, or the existence of a political structure in the areas it controls”.

With Mali’s hard-fought peace deal seemingly foundering and jihadist groups back on the offensive, the west African country could be headed for fresh chaos.

Malian, French and the United Nations forces, deployed to safeguard the country after a 2013 jihadist offensive in its vast arid north, have increasingly come under attack throughout 2016.

In late November, militants of the al-Qaeda-linked group Ansar Dine briefly seized a town alarmingly close to the capital, Bamako, raiding a police station, a bank, and a prison.

Meanwhile, pro-government militia groups and former rebels who signed a 2015 peace deal are intermittently fighting each other in the vast northern areas where the writ of the state remains tenuous, if not entirely absent. It was hoped that this peace deal would bring stability to the northern desert, the cradle of several Tuareg uprisings and a sanctuary for Islamist fighters. But since the signing of that deal, rival armed groups have repeatedly violated the ceasefire, threatening attempts to give the north a measure of autonomy to prevent further separatist uprisings.

In January 2013, French troops were deployed to repel al-Qaeda-aligned jihadists who had overrun several northern towns, joining forces with Tuareg-led rebels. At least 11 000 UN military and police eventually followed, but the jihadists were never defeated, merely displaced.

In the opinion of many Malians, the peace accord has proven to be little more than an ineffective box-ticking exercise of unfulfilled promises. Interim authorities for the restive north had been named but were not in place, while promises of joint patrols between regular Mali Army troops, pro-government militia and former rebels had not been delivered, underlining the view that the accord was struck due to outside pressure rather than by any national consensus.

Even the former colonial master France has said openly that it believes the government is not doing enough to reunite the country and bring back the separatist-leaning northern regions into the fold.

French Defence Minister Jean-Yves Le Drian said recently that “I repeat regularly to President Ibrahim Boubacar Keita that the necessary initiatives must be taken to ensure the reintegration of the people of northern Mali into the community. A former member of the French security services said (on condition of anonymity) that anyone who truly believed reconciliation with the north was possible “knows nothing about Mali”, an opinion that is widely echoed in Bamako.

Overlapping ties between jihadists and the armed groups active in the north, both former rebels and pro-government armed groups, also remain a stumbling block, with reports that militia commanders call on their jihadist allies to sabotage aspects of the deal that displease them.

Mali’s bewildering array of jihadist organisations appear to have morphed into nimble cross-border forces not plagued by the infighting that has dogged the groups that signed the peace deal.

This includes the prominent jihadist group Al-Murabitoun, which has a faction allied to Al-Qaeda, led by one-eyed Algerian kingpin Mokhtar Belmokhtar (reportedly killed in Libya in mid 2015 but lacking confirmation), while another group pledged allegiance to Islamic State, led by his former deputy Adnan Abou Walid.

As the conflict in northern Mali endures, another hot spot south of the Niger river is attracting increasing attention. It involves two main areas in the centre of the country: the Macina heartland (Fulani historical-political region, between Mopti and Segou) and the Hayré (northeast of Mopti).

The wave of dissent began shortly before the French military intervention. In early 2013, Amadou Kufa, a Fulani Islamic preacher from central Mali and an ally of Iyad ag Ghaly, the leader of Ansar Dine (one of three jihadi groups in the north), summoned his fighters to expand south beyond the area under the jihadis’ control.

However, it would be false to attribute ongoing political violence in this region simply to groups embracing jihad. At least two more rationales exist. One is about community self-defence, while the other reason involves a struggle led by Fulani herdsmen, more vulnerable than other Fulani communities of the area.

Importantly, the Fulani struggle does not exclusively target the state. Community elites, seen as state accomplices and advocates of an unsatisfactory status quo, are tacitly challenged, too, while opportunistic banditry further complicates the situation.

Recent violent clashes reflect the diversity of these dynamics. In August 2016, Nampala (in the west) suffered a deadly attack jointly claimed by the jihadis and armed groups claiming to have been defending the Fulani cause, while several months earlier, in May 2016, interethnic clashes in the Dioura area occurred between the Bambara and Fulani communities, with a reported 20 killed.

To the east, ancient tensions between Dogon farmers and Fulani herders have fuelled frequent revenge attacks. The frequency of these clashes has been exacerbated by the absence of effective state control since 2012.

And further east, the border between Mali and Niger is another hotbed of tensions, between Fulani herders and Tuareg (also called Tamasheq) herders in particular, with widespread cattle theft (organised by criminal networks), competition for grazing land and jihad intermingling.

All this violence has caused exoduses, south towards Burkina Faso and west towards the Mauritanian refugee camp at Mbera (pictured). The result is a deepening humanitarian crisis.

All this violence has caused exoduses, south towards Burkina Faso and west towards the Mauritanian refugee camp at Mbera (pictured). The result is a deepening humanitarian crisis.

In a shifting and fragmented political context, these conflicts do not work independently of each other. There have been multiple alignments among protagonists, including alliances, break-ups and short-term collaborations of convenience.

In 2012, as Tuareg separatists and then Islamic jihadis took partial control of central Mali, fractures re-opened among some elements of Fulani society, and between Fulanis and their neighbours. In the absence of the state and its army, local elites were seen as unable to protect citizens against the Tuaregs of the National Liberation Movement of Azawad (MNLA).

Those previously threatened by the MNLA perceived its ousting by the jihadist Movement for Unity and Jihad in West Africa (MUJWA) in summer 2012 as a partial relief.

These alliances with the jihadis, oscillating between pragmatism and ideological adherence, were severely punished following the French intervention. In the Hayré (north-east of Mopti), Malian armed forces reportedly carried out numerous punitive actions, including cattle theft, intimidation of local people, arbitrary arrests and occasionally (allegedly) summary executions.

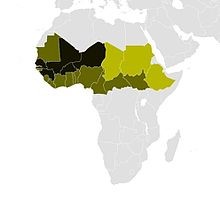

Further to the south, in the Macina heartland (between Mopti and Ségou – refer to map below)), fear of the army and a sense of abandonment by the state continues. But militancy is more consistent here, expressed in the form of jihad or ethnic identity-based discourses.

Further to the south, in the Macina heartland (between Mopti and Ségou – refer to map below)), fear of the army and a sense of abandonment by the state continues. But militancy is more consistent here, expressed in the form of jihad or ethnic identity-based discourses.

The Fulani Islamic preacher, Amadou Kufa operates here, while the recently created Alliance for the Safeguarding of the Fulani Identity and the Restoration of Justice claims to do so as well.

Through his often-fiery sermons, Kufa managed at first to convey his message of a return to a mythical time of prosperous faith, when the Fulani, now supposedly victimized, were masters of the faith.

The level of cohesion within Kufa’s movement of a few hundred fighters is subject to speculation, with his recruits seemingly pursuing reasonably fluid allegiances. Their warlike, more than genuinely jihadi, attitude makes their integration into state-backed military units an option. In recent years Mali’s central Government has specialised in delegating regional security governance to community-based outfits, with pro-government militias being more active in the north than the regular Mali army.

But Fulani personalities perceived as legitimate are rare among these youths. And attempts to recycle young Fulanis for combat within non-Fulani entities such as The Platform, a coalition of armed northern pro-government movements composed mainly of Arab and Tuareg loyalists, are hampered by mutual distrust and persistent tensions on the ground.

The Alliance for the Safeguarding of the Fulani Identity and the Restoration of Justice embodies an explicitly Fulani militant agenda. It is hard to assess its strength, following recent reports of internal factionalism. Its leader has threatened that his force will fight the Malian army should that become necessary. That has upset Fulani elites, who are accustomed to conciliation with central Government and who fear further stigmatisation of their communities in Mali.

Fear is omnipresent in the region, while the already limited economic development has stalled. Humanitarian relief is badly needed. Despite complaints against the Mali army, several Fulani civil society representatives desire the return of the state (or, rather, some form of governmental stability).

While in recent years northern Mali has been the focal point of political turmoil and of international security and military attention, today it is the centre, seen as a “buffer zone”, that is in the grip of an intense political crisis. This has possible transnational ramifications as Fulani communities on the continent are closely connected.

More generally, the situation shows how the presence of armed jihadi actors stirs up local political tensions. It also shows that political developments in this area intimately depend on specific social configurations – Gao, Timbuktu and Kidal reacted to confrontations with the jihadis in their own way.

It is essential that those who claim to want to help rid Mali of the jihadi threat recognise the diversity of these configurations and of the social experiences deriving from them in times of crisis.

Leave a Reply