Niger’s Defence Minister Kalla Mountari has formally requested that the United States commence using armed drones against jihadist groups operating on the western border with Mali, raising the stakes in a counter-insurgency campaign that has been brought to international prominence by the recent ambush of an allied U.S.-Nigerien force.

Niger’s Defence Minister Kalla Mountari has formally requested that the United States commence using armed drones against jihadist groups operating on the western border with Mali, raising the stakes in a counter-insurgency campaign that has been brought to international prominence by the recent ambush of an allied U.S.-Nigerien force.

On Oct. 4, around 50 well-armed Islamist militants killed 4 U.S. soldiers and at least 10 of their Nigerien Army partners in an ambush that exposed the dangers of the expanding U.S. presence in the largely desert nation. The 12-member US Special Forces team was reportedly in unarmored trucks when the ambush occurred. It has since been reported that the US SF soldiers were lightly armed, were without body armor, were driving unarmored 4x4s (this according to one of the Nigerien soldiers involved in the incident) and were operating without armed air cover (drones), clearly not expecting to encounter hostile forces during general patrol and intelligence gathering operations. A senior US Amy officer confirmed that dozens of similar patrols in that same general area over the course of the last six months had not encountered any enemy forces, and that “it was the judgment of the commanders on the ground that that probability was unlikely.”

Information coming to light since that mission indicates that the Special Forces team’s primary mission was to advise and assist a unit (a platoon) of 30 Nigerien soldiers. That mission did not change, but in the lead-up to the attack, the SF team was reportedly given an additional task, to assist the 30 Nigerien soldiers in support of a separate US-Nigerien team that was planning to capture or kill a high-value Islamist leader.

The episode has raised serious concerns in Washington about the readiness of US troops, and U.S. Africa Command has launched an investigation into the ambush and will review whether additional armed support is needed for these types of missions. There are around 800 US military personnel in Mali, where the US has had a mission for 20 years, and around 6000 in total within 53 countries throughout Africa. What began as a small U.S. training operation in the late 1990s has expanded to an 800-strong force that accompanies the Nigerians on intelligence gathering and other missions. Military support includes a $100million drone base in the central Nigerien city of Agadez which, however, at present only deploys surveillance drones.

The deaths of the U.S. soldiers shocked Americans, many of whom did not realise the country had such a large presence in Africa’s remote Sahel region. The incident also highlighted the “mission creep” that has set in and expanded the U.S. role in landlocked Niger, one of the world’s poorest and most insecure countries. Though U.S. forces do not have a direct combat mission in Niger, their assistance to the Niger military includes intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance in their efforts to target violent Islamist organisations.

But any growing U.S. role in Niger could prove unpopular both with Americans, many of whom are tired of costly and usually deadly foreign adventures and also in Niger, whose citizens have mixed feelings about foreign forces on their soil. Drone strikes have been controversial in other parts of the world because of the high risk of civilian casualties, and at a protest rally in Niamey over a domestic political issue three weeks after the ambush, some Nigerien demonstrators began chanting against the presence of foreign troops in Niger.

But any growing U.S. role in Niger could prove unpopular both with Americans, many of whom are tired of costly and usually deadly foreign adventures and also in Niger, whose citizens have mixed feelings about foreign forces on their soil. Drone strikes have been controversial in other parts of the world because of the high risk of civilian casualties, and at a protest rally in Niamey over a domestic political issue three weeks after the ambush, some Nigerien demonstrators began chanting against the presence of foreign troops in Niger.

Since that attack, details have begun to emerge about the likely identity of the responsible group, and its leader – Adnan Abu Walid al-Sahrawi and Islamic State Greater Sahara (ISGS)

A veteran militant leader who formerly had ties to Al-Qaeda, al-Sahrawi (pictured) has for the past two years commanded a small battalion of fighters that, in May 2015, pledged allegiance to the Islamic State militant group (IS). Since then, the group has become known as Islamic State Greater Sahara (ISGS).

A veteran militant leader who formerly had ties to Al-Qaeda, al-Sahrawi (pictured) has for the past two years commanded a small battalion of fighters that, in May 2015, pledged allegiance to the Islamic State militant group (IS). Since then, the group has become known as Islamic State Greater Sahara (ISGS).

Multiple U.S. officials have confirmed that they believe the Niger attack was carried out by the fighters of ISGS, rather than one of the multiple Al-Qaeda-linked groups that populate the Sahel, the arid belt of land across west and north-central Africa, awash with jihadis and traffickers (people and materials). Al-Sahrawi reportedly commands a small force of 40-60 militants but can count upon other likeminded allies across the region. It is likely that al-Sahrawi is among the small number of high value targets being sought by US Special Forces in Niger and Mali

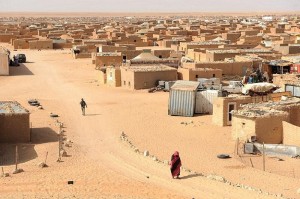

Sahrawi is thought to have been born in Western Sahara, the disputed territory on Africa’s northwest coast, and to have spent time in his early life in refugee camps in southern Algeria. Morocco considers Western Sahara to be part of its territory and many Sahrawis (as the people of Western Sahara refer to themselves – a mixture of Berber and Arab backgrounds) have been displaced via refugee camps (pictured).

Sahrawi is thought to have been born in Western Sahara, the disputed territory on Africa’s northwest coast, and to have spent time in his early life in refugee camps in southern Algeria. Morocco considers Western Sahara to be part of its territory and many Sahrawis (as the people of Western Sahara refer to themselves – a mixture of Berber and Arab backgrounds) have been displaced via refugee camps (pictured).

The Sahel is a region that has long been home to jihadi movements, and Sahrawi has well-established militant credentials. Around the time of an Al-Qaeda-backed insurgency in northern Mali in 2012, Sahrawi was then the spokesman for the Movement for Unity and Jihad in West Africa (MUJAO), one of the militant groups involved in the Mali uprising. That group would later merge with another militant organization to form Al-Mourabitoun (“The Sentinels”), an Al-Qaeda splinter that claimed responsibility for attacks including the siege of the Radisson Blu hotel in Mali’s capital Bamako in November 2015, in which 20 people were killed. Al-Sahrawi shared leadership of al-Mourabitoun with well-known one-eyed jihadi Moktar Belmoktar (pictured), until May 2015, after which he pledged allegiance to IS, which led to him being denounced by Belmoktar and leaving al-Mourabitoun.

In October 2016, the IS online mouthpiece Amaq posted a statement saying that it acknowledged the pledge of allegiance from “Katibat al-Mourabitoun” under the leadership of Sahrawi. It is difficult to gauge the real extent of any connection to IS, in a region where there are multiple radical Islamist armed groups that are active. Ideology is a factor, but more localised or economic interests may also sometimes be at play, in a region where trans-Saharan trafficking, and the funds it generates, is also a factor.

Sahrawi’s group is by no means the biggest player in the region, where Al-Qaeda through its affiliate, Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) has deep-lying roots across the Sahel region. In February 2017, AQIM merged with several other regional militant groups to form an umbrella organisation known as the Group to Support Islam and Muslims (Jamaat Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimeen, or JNIM). This organisation is ideologically opposed to IS and IS affiliated movements in the region

Given its relatively small size, it would appear to be a bold move for a group like Sahrawi’s ISGS to launch an attack on U.S. forces. Washington has 6,000 troops operating in Africa, with at least 800 in Niger, and any attack on an American patrol is likely to put the group in the crosshairs of not just the U.S. military, but its French allies stationed throughout the region.

In western Niger, gunmen on pick-up trucks and motorcycles crossed the border from Mali and killed 13 gendarmes and wounded 5, in an attack on their base. The village is around 30 kilometres from where militants killed the 4 U.S. soldiers during the 4 October ambush. Nigerien military officials confirmed the attack. The assailants drove up to the village of Ayorou, about 40 km inside Mali before springing their attack and then escaping back into Mali.

In Mali, in the first week of November, 5 Malian soldiers and one civilian driver were killed in central Mali during an ambush on a convoy of the president of the High Court of Justice, the defence ministry said in a statement. The convoy of Abdrahamane Niang was travelling between the towns of Dia and Diafarabé in the Mopti region, about 500 kilometres northeast of the capital Bamako, when it was attacked. It was not clear who was responsible for the attack, but the high-level target and the army deaths point to the deteriorating security situation in Mali due to the growing reach of the jihadist groups that continue to roam the country’s vast desert expanses.

Only days earlier, also in Mali, in the north, 3 United Nations soldiers from Chad were killed and 2 others were wounded by an explosive device as they were escorting a convoy. Since 2013, more than 80 members of the UN mission, MINUSMA, have been killed in attacks by militant groups active in the country’s north and centre, making the Mali operation the world’s deadliest peacekeeping operation.

MINUSMA said in a statement that the Chadian soldiers’ vehicle struck an explosive device (IED) between the northern towns of Tessalit and Aguelhok. Responding to the constant militant threat, the Mali Government announced that the state of emergency in the country had been extended a further year, until October 2018

Regional Background

In 2002, just months after the attacks of September 11, the George W Bush administration launched the “Pan Sahel Initiative”, a counterterrorism program in which the U.S. worked with the militaries of Chad, Mali, Mauritania, and Niger to track down criminals and terrorists in the region. Over the next several years the program expanded to include more countries, ultimately becoming subsumed into a new military command called Africom (US Africa Command) which was created in 2007.

The Sahel region countries are among the world’s poorest, with the highest fertility rates, and the lowest quality of life in the world. Poverty has created instability, with Governments exercising little control beyond the capital cities, weak State institutions, a population increasingly disillusioned with its political leadership, and Islamic orthodoxy on the rise.

The Sahel region remains vital for the U.S. military. In a letter to Congress in June 2017, President Trump notified US lawmakers that U.S. military personnel in the Lake Chad Basin “continue to provide a wide variety of support to African partners conducting counterterrorism operations in the region.” He said there were approximately 645 U.S. military personnel deployed in Niger to support these missions (the Pentagon subsequently confirmed that the number was 800), with an a An additional 300 personnel in Cameroon. Additionally, the U.S. is building a $100 million base for surveillance drones in Agadez, in the central part of Niger, to support the on-the-ground mission, all of which goes to show the U.S. presence in the region is entrenched and set to continue.

In January 2017, al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) hit the world’s headlines as it carried out a massive attack in Gao, northern Mali, killing 77 people and injuring dozens more. Al-Mourabitoun, the group of Mokhtar Belmoktar (the “most-killed” terrorist in the world, having been proclaimed dead several times since the ‘90s) claimed responsibility for the attack, saying it was punishment for Malians working with France.

From a strictly operational perspective, that attack was significant as it signaled a return to large-scale terrorist operations in an area where AQIM has historically been well established, and it signaled AQIM’s greater capacity for operations in an area where it has been progressively dislocated by the French military operations “Serval” and “Barkhane.”

A few weeks later, in February 2017, AQIM announced a merger of a few local jihadist groups into a new alliance, Jamaat Nusrat al-Islam wal Muslimeen (JNIM). This partnership included

- Islamist Tuareg organization Ansar Al-Dine;

- al-Mourabitoun, the group led by Mokhtar Belmoktar

- Katiba Macina Liberation Front of Ansar al-Dine.

This new alliance came under the command of Iyad ag Ghali, the historical leader of Ansar al-Dine. These developments were significant because as Islamic State (IS) started to lose ground in Iraq and Syria, al-Qaeda’s groups were clearly trying to capitalise on the changing situation. For AQIM itself, these developments have occurred as the organisation marks 10 years since its official creation and “rebranding”. Previously known as the Salafist Group for Preachment and Combatant (in French, GSPC, Groupe Salafiste pour la Prédication et le Combat), itself an offshoot of the GIA (the Armed Islamic Group – Groupe Islamique Armé), the most influential terrorist organization that had fought in the Algerian civil war of the 1990s.

This shift was not only a change of brand, although the symbolic dimension and the impact of publicly using the name al-Qaeda played a major role in this decision, but it was a broadening of the priorities of the former GSPC, which had suffered a number of setbacks and was on a declining path, operationally and in terms of its local popularity.

This trend had already started by the end of the 1990s, and the GSPC itself was an attempt to address it. The GSPC’s founders wanted to distance themselves from the GIA, whose indiscriminate killings had alienated many Algerians, most of whom had been sympathetic at the beginning of the Algerian civil war.

The GSPC’s localised agenda was one of the most significant issues in negotiations between the group and al-Qaeda. It took more than two years of negotiations between GSPC leadership and al-Qaeda leaders Osama Bin Laden and Ayman al-Zawahiri to bring GSPC into AQIM, with al-Qaeda leaders initially concerned the merger would be incompatible with their wider strategic goals. For al-Qaeda, its primary targets were the “far enemies” of the United States, Europe and Israel, rather than the governments of the territories in which its offshoots were operating, the so-called “near enemies” in the Sahel and Sahara regions

The merger between al-Qaeda central and the Algerian terrorists in 2006 and 2007 and the progressive convergence of interests was very much the result of al-Qaeda’s increasing strategic deterioration. It was considered a way for al-Qaeda to gain leverage in an area of strategic importance, at the doors of Europe, while for the GSPC the merger with AQIM was aimed at strengthening its regional jihadist appeal, bolstering its legitimacy and reversing the declining that had characterized the organisation since the end of the 1990s.

Despite its ambition to maintain its primary operational focus on Algeria, changing strategic circumstances forced AQIM to shift its geographical core progressively southward. Over the past decade, this gradual geographic shift of AQIM has represented one of the most significant developments in the organisation’s evolution. Although Algerian jihadism had always had a presence in the Sahel/Sahara region, both before and after the Algerian civil war, the region had never been a center of its activities, rather more a geographical appendage

As the group moved southward, its ranks also swelled as local Sahelian militants joined the organisation. However, despite this ethnic diversification, the chain of command remained firmly in the hands of Algerian militants and did not reflect the increasing diversity of the group. This created tensions, and in addition, the new Sahelian militants were more focused on spreading jihad in West Africa. This led in 2011 to the creation of the Movement for Oneness and Jihad in West Africa (MOJWA), a splinter group of AQIM that nevertheless remained in the orbit of the organisation.

Later, having been demoted following an internal reorganisation of AQIM, Belmoktar created al-Mourabitoun. The name of this new group was a sort of political manifesto, recalling the dynasty of the Almoravids who ruled in the 11th and 12th century over a unified Sahelian-Maghrebi empire stretching all the way to Andalusia (modern day southern Spain).

As such, the strategic objective was to unify the groups and the peoples of the Sahel region. Belmoktar remained in the orbit of AQIM, and enjoyed a rather fluid relationship with the organisation, before rejoining formally in December 2015.

That was also the period in which AQIM became an increasingly hybrid organisation, as the diversification of its activities became more significant. Its focus on minor jihad (armed attacks against those perceived as infidels) was balanced by the presence of more mundane illicit activities, such as kidnappings, smuggling, and controlling refugee movement towards Libya and the shores of the Mediterranean.

The local environment was conducive to these opportunities. The Sahara has been historically home to traffickers of all kinds, and the leaders of the southern regions had a comparative advantage given their in-depth knowledge of the territory. In addition, these activities provided greater revenues and strengthened ties with the local population. This was part of a long-term strategy to co-opt local groups. Indeed, these activities enabled AQIM to further its core aim of waging “wider jihad”.

The Arab Spring of 2011 had several unintended consequences, and AQIM’s increased local presence put the group in a good position to exploit the chaos that struck the region in its wake. The collapse of the Gaddafi regime in Libya in 2011 created the conditions for the spread of Tuareg fighters and weapons in the Sahel region. Many of these fighters moved to Northern Mali where they encountered the local grievances of Tuaregs there who felt discriminated against, and marginalised by, the government in faraway Bamako.

The constellation of local radical jihadist organisations, formed by AQIM, Belmoktar’s group, MOJWA and the Malian Ansar al-Dine, soon allied with the secular Tuareg of the National Liberation of the Azawad (NLA) and took control of territory in Northern Mali, with the ambition to create an Islamic state and use it as a platform to move further southwards.

Only when these groups were perceived as an immediate threat to Bamako did external countries intervene. The French military operation “Serval” disbanded the proto-Salafi state created in Northern Mali and disrupted the networks that the organisations had set up. However, the chaos in Libya also allowed AQIM to deepen its presence in the country, and many fighters started using Libya as a new logistic platform.

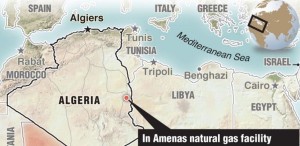

This also enabled AQIM to finally carry out a new powerful attack in Algeria (an attack in July 2013 against the major gas facility at In Amenas, organised by Belmoktar, in which around 40 foreigners were killed). This attack, which targeted international oil companies and their employees, was a return to AQIM’s focus on striking locally with a global impact.

The In Amenas attack was nevertheless an exception, as the new operational trends of the organisation were increasingly focused on West Africa. Between the end of 2015 and early 2016, the group carried out massive terrorist attacks targeting hotels and holiday resorts in Bamako (Mali), Burkina Faso and Ivory Coast. This further Africanisation of the operational profile of AQIM and its affiliate is the result of its emerging rivalry with IS.

The emergence of IS in the wider jihadist world was another unintended consequence of the Arab Spring. IS evolved from an off-shoot of the al-Qaeda presence in Iraq and Syria (Al Qaeda in Iraq – AQI). Members of this group severed their ties with al-Qaeda “Central” and its proxy in Syria (al-Nusra Front – Jabhat al-Nusra) and created a group characterised by further radicalisation, an aggressive social media campaign, and an even more violent approach to jihad.

IS also represented a threat to AQIM in operational terms, including the recruitment of youth from the region. Tunisians and Moroccans accounted for a very significant part of the foreign fighter ranks of IS, recruited through its presence in a number of strategic regional theatres, such as Libya and Tunisia. IS also became a magnet for local minor leaders who saw a pledge of loyalty to IS to boost their status, something that created a number of problems for Belmoktar’s al-Qaeda aligned organisation. IS’ aggressive use of the media and a powerful brand fueled a sort of competition, forcing AQIM to adapt some of its media strategies to those of its more radical jihadist rival.

IS also represented a threat to AQIM in operational terms, including the recruitment of youth from the region. Tunisians and Moroccans accounted for a very significant part of the foreign fighter ranks of IS, recruited through its presence in a number of strategic regional theatres, such as Libya and Tunisia. IS also became a magnet for local minor leaders who saw a pledge of loyalty to IS to boost their status, something that created a number of problems for Belmoktar’s al-Qaeda aligned organisation. IS’ aggressive use of the media and a powerful brand fueled a sort of competition, forcing AQIM to adapt some of its media strategies to those of its more radical jihadist rival.

Ten years on, in 2017 AQIM has evolved into a very different organisation from what it was in early 2007. Although its leadership remains Algerian, Algeria no longer represents AQIM’s main focus. AQIM is now more of a regional franchise, the center of gravity for several local groups, and part of the wider al-Qaeda global project.

Moreover, AQIM represents a regional counterbalance to IS, and the rivalry between the two organisations has been a significant feature of the regional geostrategic environment. As IS declines, it is likely that many IS fighters will move closer to al-Qaeda-linked groups once again. In addition, with the decline of IS, AQIM is likely to return to regional North African theatres, among them Libya.

In Mali, the establishment of JNIM shows that AQIM intends to capitalise on the’ increasing weakness of IS and bring together in a systemic way those organisations that had loosely gravitated to AQIM over the last few years. While many previously collaborated on a tactical level with AQIM, they did not always follow its strategic direction, directives, and operational (tactical) priorities. AQIM’s operational return to Northern Mali now shows that the group intends to reassert itself in those territories where it had an established presence prior to the French-led military operation in 2013.

That said, while AQIM does not appear to have the capacity to establish a Salafi-jihadist state in the region, it will continue to represent a significant asymmetrical and hybrid threat, mixing minor jihadist operations with criminal activities to bolster its finances and further its ultimate goals of fighting “near enemies” such as regional governments and actors such as Libya’s General Khalifa Haftar, and its traditional “far enemies” in the West.

Going Forward: G5 (Mali, Niger, Burkina Faso, Chad and Mauritania)

As 2017 draws to its conclusion, in the first week of November, a joint anti-jihadist force linking countries in the Sahel began operation. Several hundred troops have been deployed in the initial operation. This G5 force will provide a show of strength and demonstrate presence in the Mali, Burkina and Niger border regions and impede freedom of movement, according to the regional Governments comprising the force.

The world’s newest joint international force, the five-nation G5 Sahel plans to number up to 5,000 military and police, and civilian support staff, by March 2018. The 5,000 personnel will include two Infantry battalions each from Mali and Niger and one battalion each from Burkina Faso, Chad and Mauritania. The force has been placed under the leadership of a Malian general, Didier Dacko, although for the time being the national contingents will not be integrated.

The idea behind the force dates to November 2015, as countries on the rim of the Sahara grappled with the escalating wave of jihadist attacks. The G5 Sahel’s activities will be initially confined to Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger, where the three central governments have weak control over remote areas.

France, the G5 Sahel’s most vocal backer, has an additional 4,000 military personnel in the Barkhane force., and its role in the G5 alliance will be to provide advice and intelligence, with air, artillery and some logistics support. About a hundred French troops will be involved in this context.

However, funding remains a major concern for the G5 Sahel military alliance. Estimates for the first year of operations are put at €400+ million (around USD500 million), although French officials say the budget can be brought down to around €240 million (around USD280 million). At present, the G5 has funding pledges of around €100 million, including €50 million from the five countries themselves, plus USD60million (€50 million) promised by the United States Government at the end of October. A donor conference will be held in Brussels in December.

OAM Principals have extensive operational experience throughout the West Africa, Sahel and Sahara region and understand the risks inherent to international management and personnel when working in the region.

Leave a Reply