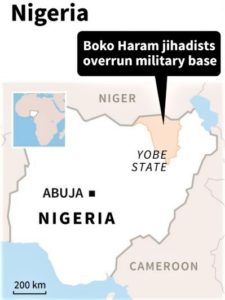

In NIGERIA, it has been reported that hundreds of Nigerian troops are missing after Boko Haram jihadists overran a military base in the remote northeast, in the second major assault on the Nigerian armed forces in two days. The jihadist militants, reportedly in the hundreds, attacked and reportedly overran the Army base, holding more than 700 soldiers, a battalion sized unit forming part of the 81st Division Forward Brigade, in Yobe state in a coordinated attack that lasted from early Saturday evening (14th July) until mid-morning of the following day (Sunday 15th July). Military sources in Nigeria stated that of the more than 700 troops known to have been in the base, only 100 have returned to the base following the attack. This second attack in 24 hours took place after Boko Haram fighters ambushed a military convoy in neighbouring Borno state.

In NIGERIA, it has been reported that hundreds of Nigerian troops are missing after Boko Haram jihadists overran a military base in the remote northeast, in the second major assault on the Nigerian armed forces in two days. The jihadist militants, reportedly in the hundreds, attacked and reportedly overran the Army base, holding more than 700 soldiers, a battalion sized unit forming part of the 81st Division Forward Brigade, in Yobe state in a coordinated attack that lasted from early Saturday evening (14th July) until mid-morning of the following day (Sunday 15th July). Military sources in Nigeria stated that of the more than 700 troops known to have been in the base, only 100 have returned to the base following the attack. This second attack in 24 hours took place after Boko Haram fighters ambushed a military convoy in neighbouring Borno state.

Military sources have admitted that the base commander and most of the troops fled the battle, confirming yet again the poor level of command, poor level of training and operational capability, and most importantly, the low esprit of the soldiers, most of whom had only recently deployed to the base from Lagos. Abandoning a well defended military position, where the defenders outnumber the attackers by 3:1, reaffirms the difficulties the Nigerian Army is confronting as they try to fight a counter insurgency campaign for which they are ill-suited.

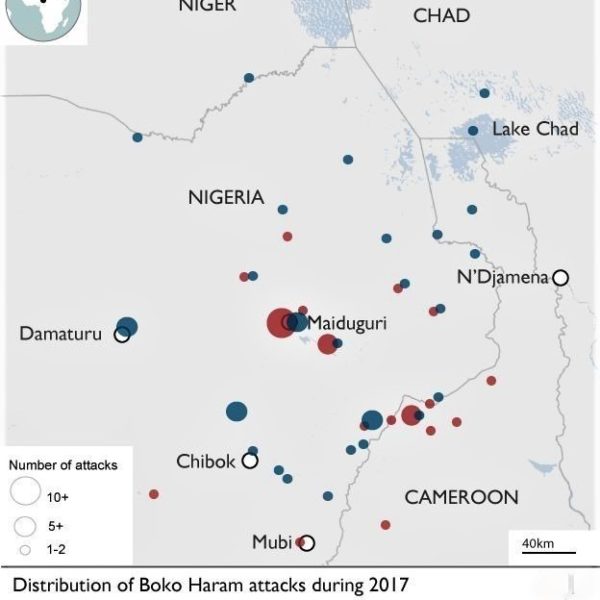

The attack has been attributed to the Abu-Mus’ab Al-Barnawi faction of Boko Haram, which is known for targeting Nigerian forces, unlike the Abubakar Shekau faction, which has embarked on a terror and bombing campaign targeting civilians and soft targets. The jihadist attackers reportedly came from the Lake Chad region on vehicles to attack the base.

A day earlier, more than 20 Nigerian soldiers went missing, presumed killed or captured, after an estimated 100 Boko Haram fighters ambushed their convoy outside Bama, in Borno state, about 45 kilometres from the principal regional town of Maiduguri, destroying at least 8 military vehicles during the attack.

As a direct consequence, the Nigerian Army Chief of Staff, Lt-General Tukur Buratai, on July 27th circulated a set of operational guidelines warning operation field commanders of serious consequences should they abandon their positions and their men in future confrontations with Boko Haram. The memo was disseminated across all military formations and locations, countrywide.

Using particularly strong language, the General bemoaned the lack of “reasonable resistance” in the face of Boko Haram attacks, actions which portrayed the commanders and their troops as “incompetent and cowardly” and consequently warned them that they would be subjected to “harsh punishments” under the Armed Forces Act. Such punishments could render any officer of soldier “liable to suffer death or any less punishment provided by the Act”.

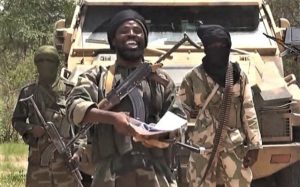

Earlier this year Boko Haram leader Abubakar Shekau released another video message, amid the surge in violence throughout Nigeria which continues to serve to ridicule the Nigerian government’s claim that the jihadist group is defeated.

Earlier this year Boko Haram leader Abubakar Shekau released another video message, amid the surge in violence throughout Nigeria which continues to serve to ridicule the Nigerian government’s claim that the jihadist group is defeated.

“We are in good health and nothing has happened to us,” said Shekau in the video message spoken in the Hausa language common across northern Nigeria. In the video, Boko Haram fighters in ragged clothing were shown shooting from the back of battered pickup trucks.

Boko Haram has attacked convoys of Nigerian soldiers and has deployed suicide bombers into crowded markets in towns across northeast Nigeria, while Nigerian President Muhammadu Buhari continues to expound the Government line that “isolated attacks still occur, but even the best-policed countries cannot prevent determined criminals from committing terrible acts of terror”.

Shekau, a leader known for his lengthy, excitable video messages, took over Boko Haram in 2009 after the death of its founder Muhammad Yusuf. Boko Haram, whose Islamist insurgency has left at least 20,000 dead in Nigeria since it began in 2009, has long been fractionalised, and in 2016 it suffered a major split, when the Islamic State-aligned group recognised Yusuf’s son, Abu Mus’ab al-Barnawi, as leader.

Attacks in Nigeria reflect the diversity of Nigeria’s security threats that persist in the absence of a well thought out counter insurgency approach, a robust police force and an efficient judicial system. To add to the Boko Haram woes confronting Nigeria, the country is also in the grip of a secondary security crisis, as nomadic herders and sedentary farmers fight over land in an increasingly bloody battle for resources.

Rural communities have been under siege for several years from cattle rustlers and kidnapping gangs, who have raided local communities, killing, looting, and burning homes. To defend themselves, villages and herders formed vigilante groups, but they too are often accused of extra-judicial killings, provoking a bloody cycle of tit for tat retaliatory attacks.

President Buhari has been criticised for his failure to curb the violence, which is becoming a key election issue ahead of the upcoming presidential polls scheduled for early 2019. In reality though, military and police assets are overstretched in Nigeria, as they combat multiple threats, from militants and pirates in the oil-rich south, to the Boko Haram movement in the east, and the bloody battle between herders and farmers spanning the vast central Nigeria region.

In May, suicide bombers killed at least 60 people at a mosque and a market in Mubi, some 200km from the Adamawa state capital, Yola, in northeast Nigeria, in a twin attack that came only one day after US President Donald Trump had pledged greater support to fight the Islamist militants. Mubi has been repeatedly targeted in attacks blamed on Boko Haram since it was briefly overrun by the militants in late 2014.

Following President Muhammadu Buhari’s trip to the US in the United States at the end of April, President Trump pledged more support to Nigeria in the fight against Boko Haram, while also reaffirming Nigeria’s regional leadership role.

Following President Muhammadu Buhari’s trip to the US in the United States at the end of April, President Trump pledged more support to Nigeria in the fight against Boko Haram, while also reaffirming Nigeria’s regional leadership role.

Nigeria has purchased 12 A-29 Super Tucano light fighter aircraft in a $500m deal (a deal which had previously been blocked by the Obama Administration on human rights grounds). Trump indicated a further order for attack helicopters was also in the pipeline. “These new aircraft will improve Nigeria’s ability to target terrorists and protect civilians “Trump told a joint news conference with Buhari in Washington, before Buhari returned home.

Having advanced high-tech military equipment is one thing, but the US Defence attaché in Abuja recently questioned Nigerian military strategy and tactics as they confront Boko Haram’s insurgency, expressing the view (supported by a number of international military and defence specialists) that the Nigerian Army is constrained in its counterinsurgency skills through its focus instead on conventional warfare.

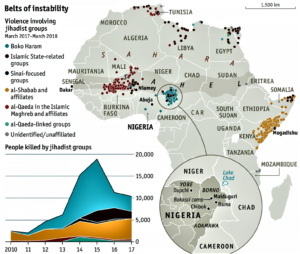

Nigeria’s main NE city, Maiduguri, sits at the centre of a line of jihadist campaigns stretching in two broad bands across Africa on either side of the Sahara, with the northern belt stretching along the Mediterranean coastline from Egypt, through Libya and Tunisia, and reaching to Algeria, while the southern band extends from Somalia and Kenya in the east, through Nigeria and Niger, to Mali, Burkina Faso and Senegal in the west (see map).

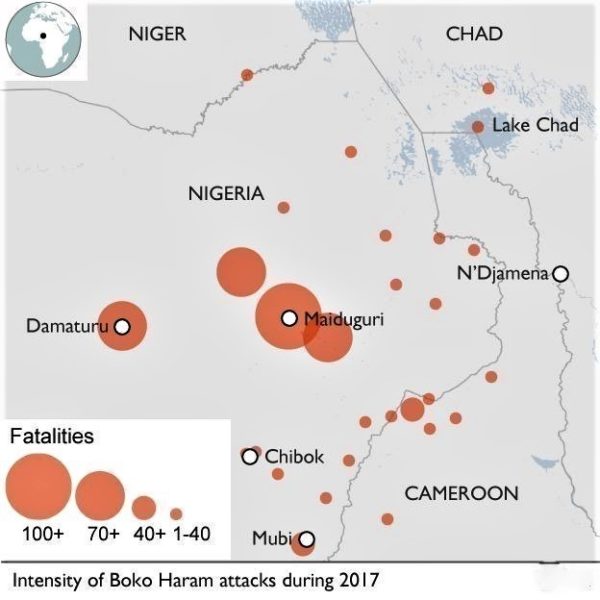

Despite the fact that in 2017 more than 10,000 people, most of them civilians, were killed, the area is rarely in the international eye, despite Boko Haram becoming the deadliest terror group in the world and being home now to the largest group of Islamic State (IS) members and sympathisers outside of Iraq and Syria, drawing in specialist troops from America, France, Britain and Germany.

Despite the fact that in 2017 more than 10,000 people, most of them civilians, were killed, the area is rarely in the international eye, despite Boko Haram becoming the deadliest terror group in the world and being home now to the largest group of Islamic State (IS) members and sympathisers outside of Iraq and Syria, drawing in specialist troops from America, France, Britain and Germany.

In the last decade, the number of violent incidents involving jihadist groups in Africa has increased by more than 300%, while the number of African countries experiencing sustained militant activity regionally has more than doubled to 12 over that decade. Despite the French maintaining a force of 4500 men under Operation Barkhane, there are increasing calls from commanders on the ground for additional troops (typical “mission creep” which in counterinsurgency is generally unavoidable).

Indigenous Islamist groups across the Sahel and Sahara, from east to west Africa, have pledged loyalty to al-Qaeda or IS. These groups include al-Shabab in Somalia, Boko Haram in Nigeria, and Jama‘a Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin in Mali. Since the overthrow by NATO of Muammar Gaddafi in 2011, many of the regional jihadi militias have been strengthened by the huge arsenals that were looted from Gaddafi’s armouries, and financed by smuggling networks moving people and drugs across the region to the Mediterranean. Nigeria, as Africa’s most populous nation with an estimated 180-200 million people, and with a huge landmass, is engaged in perhaps the most important battle against insurgency. In the last year Nigeria has overtaken South Africa to become the largest economy in Africa, and the view gaining traction in Sahel and Sahara Africa is, if a country with such financial and manpower resources cannot contain the jihadist threat, how can Africa’s poorer and less militarily capable States do better?

The Nigerian government continues, despite clear evidence to the contrary, to insist that the war against Boko Haram has been won. Maiduguri was the birthplace of Boko Haram, founded by the followers of charismatic Islamic preacher Mohammed Yusuf, who started his religious school and mosque in Maiduguri in 2002

Yusuf exhorted his followers to reject the state, since it is created by man, not God, and any Western knowledge that contradicted his interpretation of Islam. Nigeria’s northern states have long enforced sharia, or Islamic law, but according to Yusuf, that interpretation and implementation was not strict enough. Among his early demands was a ban on secular schooling (the group’s name, Boko Haram, has been translated as “Western education is a sin” in Hausa but literally means “books are forbidden” – books other than the Koran).

Yusuf exhorted his followers to reject the state, since it is created by man, not God, and any Western knowledge that contradicted his interpretation of Islam. Nigeria’s northern states have long enforced sharia, or Islamic law, but according to Yusuf, that interpretation and implementation was not strict enough. Among his early demands was a ban on secular schooling (the group’s name, Boko Haram, has been translated as “Western education is a sin” in Hausa but literally means “books are forbidden” – books other than the Koran).

Before the end of that decade, Yusuf’s adherents were attacking the police and army, and killing clerics who disagreed with his interpretation of Islam. The Nigerian police arrested and then killed Yusuf in front of a crowd outside the police headquarters in Maiduguri (though the Government insisted that Yusuf was shot while trying to escape), forcing Yusuf’s followers into hiding before emerging under the command of Abubakar Shekau.

Announcing themselves on the international stage, in 2011 Boko Haram militants attacked the headquarters of the Nigerian police (pictured) and the UN building in Abuja, Nigeria’s capital.

Three years later, by the end of 2014, they had overrun large parts of three states in north-eastern Nigeria, had gained international notoriety after kidnapping 276 schoolgirls from Chibok (leading US First Lady Michelle Obama to engage in the ultimately ineffective “Bring back our girls” campaign) and were fighting their way into Maiduguri. Nigeria’s army, demoralized and undermanned through corruption in the Military High Command, was outgunned and outfought, while military units were filled by “ghost soldiers” whose pay was being pocketed by their commanders.

Boko Haram, now renamed Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP) after pledging allegiance to Islamic State in Syria and Iraq, thrived on chaos, rather than implementing good governance in the areas it controlled, and embarked on a campaign of outright terror, bombing mosques and markets, massacring villagers and abducting women and children, with young girls kept or sold as sex slaves or as reluctant suicide bombers. UNICEF, the UN children’s agency, estimated that in 2017, Boko Haram strapped bombs onto at least 135 children.

To counter Boko Haram terror, thousands of villagers and residents of Maiduguri joined a self-defence militia, the Civilian Joint Task Force (CJTF – photo) to protect the city, while incoming President Muhammadu Buhari, a northerner and former military dictator, ordered his Generals to relocate their headquarters to Maiduguri. The neighbouring states of Chad, Niger and Cameroon contributed troops to the multinational force, and within months the army had recaptured most big towns, pushing the insurgents into the thick forests or into Lake Chad, a mass of swamps where the borders of the four countries meet.

Despite ongoing and repetitive claims from Abuja, Boko Haram insurgents still control much of the countryside and the more remote villages, while the Army continues to hold the main towns and the roads connecting them. Regional defence analysts estimate that in its entirety, the manpower strength of Boko Haram (both factions) is currently around 5,000 combatants.

Despite ongoing and repetitive claims from Abuja, Boko Haram insurgents still control much of the countryside and the more remote villages, while the Army continues to hold the main towns and the roads connecting them. Regional defence analysts estimate that in its entirety, the manpower strength of Boko Haram (both factions) is currently around 5,000 combatants.

Boko Haram (ISWAP) has refined its tactics and now is skilled in the assembly of IEDs to be used as roadside bombs and has upgraded its operational skills such as ambushing convoys, attacking military defensive positions, and creating fear and uncertainty throughout the NE region. Since its alignment with combat hardened IS fighters in Iraq and Syria, it has undoubtedly received training and advice from elements of this group, while it has been reported that a number of foreign fighters (probably Arabs such as Libyans and Tunisians, in addition to closer regional supporters from Mali and Niger) have been seen within its ranks.

The Nigerian army remains overstretched, underequipped and demoralised, with an estimated 35,000 troops (three Divisions) deployed to the north east regions. Army HQ never provides killed and wounded troop numbers, though some reliable estimates put losses in the region of 300 soldiers killed with around 1500 wounded (a killed:wounded ratio of 1:5).

ISWAP has learned from the mistakes of the early Boko Haram maladministration, and has started to consolidate control of border villages, levying taxes and extorting money from passing road traffic, while in exchange offering security and a semblance of justice in areas that have fallen outside the control of the state. Although as an insurgent group it cannot hold territory against the concerted strength of the Nigerian army, it is building what could be described as a new mini-Caliphate, emulating that established by IS (and since dismantled by the Coalition military campaign in Iraq and Syria).

As a tool in counterinsurgency, winning hearts and minds plays a crucial role in bringing the people onside, but in Nigeria, it is claimed by some that the Army did the very opposite, as it systematically cleared people from the countryside, burnt their villages and packed them into squalid camps in Maiduguri and other garrison towns, with up to 2.4 million people displaced by the fighting, not only in Nigeria but across the borders in neighbouring countries. The army contends that it was necessary to move people away from the fighting, to protect them and to deny the jihadists food and shelter, a classical counterinsurgency strategy.

Indiscriminate killings by the army and the forcing of people into garrison towns are undoubtedly adding fire to the insurgency, with almost total unemployment in the holding camps, where access is through checkpoints manned by the army and CJTF, who demand bribes, and where, according to Amnesty International, many women and girls have been raped in the camps, while certainly hundreds of people confined in them have died of starvation, poor hygiene conditions, and a general lack of adequate medical care.

In areas affected by Boko Haram outside the camps, schooling, health care and other public services have virtually disappeared, leading to a recruiting paradise for Boko Haram, who exploit the dissatisfaction of the local communities remaining outside the camps, in the forest and savannah. The UN Development Programme found that nearly three quarters (+ – 75%) of the people who have joined jihadist groups in Africa have done so in response to brutality by the security forces.

The US and Britain are currently engaged in training programmes with the Nigerian military and both countries provide intelligence, while US Special Forces have conducted joint patrols with the Niger army, and France through Operation Barkhane conducts extensive operations across the Sahel. Western nations (US, Britain, France and Saudi Arabia principally) have agreed to contribute funds to the recently established G5, a regional counterterrorism force with troops from Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania and Niger, though Mali’s President has recently complained publicly that only a small amount of the promised +$450 million (sufficient to sustain the force for one year) has actually been received.

In NIGER, as Europe seeks to stem the flow of illegal immigrants across the Mediterranean, Italy announced in December 2017 its intention to send up to 500 troops, including Special Forces, to Fort Madama, a French-built military outpost sitting astride key smuggling routes in Niger, 100 kms south of the Libyan border, to confront people-traffickers who send Africans across the Sahara into Libya. Fort Madama was established as a French Foreign Legion outpost in the 1930s.

Despite some resistance from Opposition parties, in January 2018 Italy’s Parliament eventually approved the troop deployment.

The strategy of forward deployment reflects the Italian Government’s view that Libya’s desert frontier is now Europe’s southern flank, a gateway for migrants heading across the Mediterranean, that must be sealed. However, in the view of Niger President Mahamadou Issoufou, “the border with Europe, in reality, is Niger and Chad, taking into account the power vacuum, the chaos there is in Libya”.

To add to the increasing security issues in Niger, Algeria has been rounding up thousands of Nigeriens, including some who have lived in Algeria for decades, and abandoning them along the Nigerien border, piling further pressure on one of the world’s poorest countries. Niger is already dealing with Boko Haram in the east, the IS-linked Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS) in the north-west, and a chaotic Libya to the north.

Italy has already trained Libyan coastguards to intercept migrants setting off in perilous inflatables, and the current mission evolution is seen as a way to stop Libya becoming a bottleneck for stranded migrants.

The Italian military mission follows a French request for help to support the 4500 French soldiers already deployed to Mali and Niger to fight jihadi insurgents in the Sahel region. Italy joined other European leaders and the governments of Mali, Niger, Chad, Burkina Faso and Mauritania at a conference outside Paris earlier this year, to discuss joint efforts to crack down on IS-aligned terrorists in the region.

The Niger mission comes after a series of political disagreements between Italy and France, going back to Italy’s anger in 2011 over French pressure to oust Libyan dictator Muammar Gaddafi (which Italy saw as damaging to their financial interests and to ENI’s oil extraction activities in the country). Italy subsequently refused to aid France when that Government deployed troops to Mali in 2013 to counter the ever-growing jihadist threat. The new easing of tension follows closer military ties and increasing European military integration, prompted primarily by Britain’s impending exit from the EU.

Despite the thawing in military collaboration, Italy has been suspicious of France’s support for General Khalifa Haftar in eastern Libya (Benghazi), where the two nations’ energy companies (ENI and TOTAL) vie for influence.

Italy’s military chief of staff, General Claudio Graziano, stated at the outset that the Italian mission will not be a combat force, but rather will focus on training Nigerien soldiers to tackle traffickers and jihadists. This may be somewhat optimistic, as the well-armed and motivated Islamist militias holding sway and generally moving freely throughout the Sahel will certainly be prepared to take on the Italian troops. An Italian Defence Ministry source in Rome said the mission would be simply men and vehicles.

Italian troops will be well aware that 4 US Special Forces (“Green Berets”) soldiers were killed in Niger in October 2017 by an estimated 50 Islamic State-affiliated militants who ambushed their convoy with rocket-propelled grenades and heavy machineguns. The mission will ramp up as Rome diverts about half the 1500 troops it has stationed in Iraq and a number from Afghanistan as that mission winds down.

Nigerien President Issoufou has said that foreign troops working in his country should limit themselves to providing training, equipment, and intelligence, and not be engaged in fighting the jihadists, a somewhat simplistic understanding of the threat presented by Islamist groups roaming his country. “We’re not asking foreign forces to fight in our place. We’re battling to ensure the security of our country. What we ask of our allies is to help us reinforce the operational capacity of our security forces through training, equipment and intelligence.”

In MALI, the Government announced that the army will deploy additional patrols in the centre of the country, in the continuing operation against jihadists, as the government expressed continuing concern over extreme instability in the area. Recently appointed Prime Minister Soumeylou Boubeye Maiga (formerly the Mali Defence Minister) announced that the country requires urgent measures to be taken, to address Al-Qaeda-linked groups who control territory in the area.

In MALI, the Government announced that the army will deploy additional patrols in the centre of the country, in the continuing operation against jihadists, as the government expressed continuing concern over extreme instability in the area. Recently appointed Prime Minister Soumeylou Boubeye Maiga (formerly the Mali Defence Minister) announced that the country requires urgent measures to be taken, to address Al-Qaeda-linked groups who control territory in the area.

It was announced that the eventual deployment of up to 1,000 Mali Army soldiers will be aimed at assuring the security of the population, as well as fighting the jihadists. The security plan includes foot and motorbike patrols in the community, emulating the modus operandi of the various jihadist networks in the area, while a mobile support structure would provide basic services, health, and education especially, to populations excluded from access due to living in high risk areas. Islamists in central Mali have exploited the long-simmering ethnic tensions as the state retreated, propagating violence that was once limited to the north.

Jihadism in the Sahel destabilises those countries (Mali, Niger, Chad and Mauritania) with some of the fastest growing populations, and it is understood that if these countries descend into chaos, Europe can expect millions more refugees. The rise of jihadism in Africa is rooted in bad governance, exacerbated by population pressure and climate change. When the state is seen as corrupt and predatory, the promise of religious justice by the emerging Islamist groups can sound appealing.

Currently in Mali, Western forces are helping to hold the fragile region together, but since the death of the 4 US Special Forces operators in Niger in November 2017, it seems that US troops have been ordered to take fewer risks, while their commanders have been told to plan for a possible cut of up to 50% to the number of Special Forces assigned to the region.

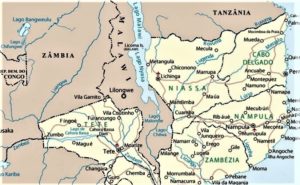

In MOZAMBIQUE, the government has been shaken by beheadings and other deadly attacks by suspected Islamic extremists belonging to the emerging Al Sunnah wa Jama’ah in a northeastern region where substantial offshore reserves of natural gas are about to be extracted. Over the course of this year, men with machetes have spread terror in several villages in Cabo Delgado province, along the border with Tanzania, beheading 10 people in one attack, hacking others to death (including children) and burning vehicles and homes.

In MOZAMBIQUE, the government has been shaken by beheadings and other deadly attacks by suspected Islamic extremists belonging to the emerging Al Sunnah wa Jama’ah in a northeastern region where substantial offshore reserves of natural gas are about to be extracted. Over the course of this year, men with machetes have spread terror in several villages in Cabo Delgado province, along the border with Tanzania, beheading 10 people in one attack, hacking others to death (including children) and burning vehicles and homes.

At least 35 people have died since May, and security forces have killed 11 suspected militants, according to the Government in Maputo. In early June, local staff at Anadarko, the international oil and gas company, refused to go to work because they feared an attack, and the company then asked its foreign staff not to leave their compound. The US embassy subsequently advised its nationals to leave the province immediately.

The violence started in late 2017 and included a deadly attack on police in Mocimboa da Praia town in October 2017, prompting the Mozambican government to launch counterterrorism operations in Muslim communities, where there have been long standing complaints of Government neglect.

Local residents called the attackers “al-Shabab,” although the extremists have no known formal link to the Islamic extremists in Somalia, but the emerging insurgency by a shadowy band of young Mozambican Muslims has intensified worries that Islamic extremism may have found a new beachhead, this time in southern Africa. Even so, the killings in Cabo Delgado appear localised and the attackers, whose fundamentalist ideology seemed undeveloped to some observers, could also be driven by ethnic and economic resentments, as well as the interests of criminal syndicates. The group remains somewhat of a mystery because it has not made any public declarations about its motives or loyalties, making it hard for defence and security analysts to understand what objectives it may have.

Although Mozambique’s population of 30 million is predominantly Christian, Muslims (primarily of the Sufi creed) make up a substantial minority of nearly 20 percent (6 million), most of whom live in the northern coastal areas, where social development has been neglected in comparison to development in southern areas, including in the capital of Maputo. During the years of the war for independence from the Portuguese in the 1970s, Frelimo, the now ruling party, suppressed Islamic and other religious activities, but eventually officially recognised freedom of religion as the party moved away from its early Marxist policies.

The U.S. Embassy recently warned of information indicating the possibility of attacks on government and commercial centers in Palma, a district headquarters in Cabo Delgado that would be a base for the natural gas industry that will boost Mozambique’s economy, but has also raised questions about how any windfall will be distributed equitably in the impoverished, corruption-prone country.

Major international oil and gas operators, including ENI of Italy, and Anadarko and ExxonMobil of the US, are setting up facilities in Cabo Delgado. Wentworth Resources, a Canada-based company, stated that security problems in the Mocimboa da Praia and Palma regions had prevented safe access for their workers, declaring the situation remains challenging. Natural gas facilities and international companies have so far not been attacked in the violence, which initially concentrated on security and State interests, but has this year shifted to civilians. Mozambican officials said the militants are now attacking villagers instead of targeting the security forces, because they have been weakened by a security crackdown, while independent analysts speculated that suspected collaborators with the government have now been targeted, or that the victims are ethnic Makondes, under assault from ethnic Mwanis who feel marginalised.

As with the similarities with Boko Haram in Nigeria (though on a much smaller scale at this stage), many militants are disaffected by severe poverty and high unemployment, and some have reportedly traveled to regional countries, including Kenya, Tanzania and further afield to Congo (DRC) and Somalia, for religious or military training, and some have been allegedly influenced by the followers of Sheik Aboud Rogo, a Kenya-based Muslim cleric who allegedly had links to al-Shabab in Somalia, before being killed by suspected Kenya Government agents in 2012, which led to violent protests by his supporters in Mombasa.

As with the similarities with Boko Haram in Nigeria (though on a much smaller scale at this stage), many militants are disaffected by severe poverty and high unemployment, and some have reportedly traveled to regional countries, including Kenya, Tanzania and further afield to Congo (DRC) and Somalia, for religious or military training, and some have been allegedly influenced by the followers of Sheik Aboud Rogo, a Kenya-based Muslim cleric who allegedly had links to al-Shabab in Somalia, before being killed by suspected Kenya Government agents in 2012, which led to violent protests by his supporters in Mombasa.

The group in northern Mozambique currently is assessed to be as many as 1500 militants, though this is difficult to confirm as they operate in largely autonomous cells. The Mozambican government is slowly coming to the realisation that it cannot stamp out the problem simply with harsh security crackdowns, but that any effective strategy will need to address the root social causes of the bloody unrest, before extremism takes hold strongly. But in its initial clumsy kneejerk response, state security authorities responded forcefully to the emergence of this threat, arresting hundreds of men and women, closing a number of mosques and discouraging Muslims from wearing religious garb, prompting a number of influential Muslim leaders to warn the Mozambique government not to alienate all Muslims because of a fringe group’s activities.

There are economic as well as religious and security issues at play. Cabo Delgado province borders Tanzania and is home to 2.3 million people, 58% of whom are Muslim. In the past few years massive oil and gas reserves have been discovered. These resources are set to lead to the development of a multibillion dollar industry in Cabo Delgado, and a rosier future for Mozambique’s economy.

BACKGROUND

The appearance of Al Sunnah wa Jama’ah (People of the Sunnah community) appears to be very similar to what has been seen with Boko Haram in Nigeria, starting as a religious sect which transformed into a guerrilla group as it exploited and fed on community anger with the authorities. The group is also known as Al-Shabab, even though it appears to have no discernible connections (for the time being) with the Somali al-Shabab movement. The sect’s initial goal was originally to see sharia law (Islamic law) implemented in the region, similar to what is in place in parts of Nigeria. It tried to do so by withdrawing from both society and the state, whose schooling, health system and laws it rejected, a posture that led to tension with the Government.

Despite the movement’s lofty ideals, some elements of Mozambique’s security establishment claim that the movement is motivated by money as opposed to social grievances, accusing the group of being involved in illegal mining, logging, poaching, and contraband, earning millions of dollars a week through criminal activity. But these assertions are not backed by any hard evidence and it is difficult to imagine that a guerrilla group allegedly earning substantial income from such activities would embark on any uprising with machetes and very few guns.

The genesis of the current crisis has its roots in the militarisation of Al Sunnah wa Jama’ah in 2016, when tensions with other Muslims and the state increased and the movement began to prepare for armed action, which came in October 2017 when a group of 30 men attacked three police stations in Mocimboa da Praia, killing 2 two policemen and stealing arms and ammunition before occupying the town itself, promising not to harm the residents, before eventually withdrawing to set up military bases in the forest (again, a strong parallel with Boko Haram in Nigeria).

Mozambique has responded to the latest crisis by entering into mutual security agreements with the governments of Tanzania, Congo (DRC) and Uganda, establishing a regional military command, and deploying additional troops into the North. How it addresses the growing security threat and the increasing agitation for an equitable share of the future prosperity promised by the huge reserves of natural gas will determine whether this home-grown group of Muslim militants will disappear or evolve into a more dangerous threat to the State.

OAM Principal John Gartner has worked extensively throughout Nigeria, the Sahel and Sahara region, and Southern Africa, including Mozambique, and maintains a network of well qualified advisers and consultants across the region.

Leave a Reply