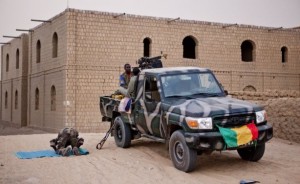

At least 17 Mali soldiers were killed and nearly 40 wounded in an attack on an Army base in central Mali on the 19th July. A Government official in Bamako confirmed the attack, with the assailants reportedly arriving in dozens of pickup trucks and motorcycles and taking over a military base at Nampala (located in semi-desert scrubland close to the Mauritania border), causing the Govt. soldiers to abandon their positions and allowing the attackers to seize a quantity of weapons and vehicles before withdrawing.

The National Alliance for the Safeguarding of the Peul Identity and the Restoration of Justice (known local as ANSIPRJ) later claimed responsibility for the attack, though shortly after this claim, Islamist militant group Ansar Dine also claimed responsibility, through its Macina Battalion.

Eventually, Army spokesman Suleiman Maiga admitted that the raiders had briefly taken control of the Nampala base while Malian troops had retreated to nearby Diabaly to “regroup”. The Mali military claimed that three groups staged the raid: Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) attacked from the north, with the Macina Liberation Front (linked to Ansar Dine) outside the town in ambush for any military reinforcements, and the ethnic Peul group (ANSIPRJ) attacking from the southeast.

His comments tie in with the earlier claims of responsibility by both Ansar Dine, which said its Macina Battalion staged the raid, and by ANSIPRJ

With the insurgency growing and attacks against the UN and Mali Army continuing, the Algiers Accord signed between the Mali government and two coalitions of armed groups in northern Mali is under stress.

The Coordination of Movements of Azawad (CMA) takes its cue from the National Liberation Movement of Azawad (MNLA), drivers of the Tuareg insurgency in 2012, which continues to pursue a separatist agenda, while another group, the “Platform”, is a loose collection of armed movements which is generally seen as pro-government but from diverse constituencies and driven primarily by local agendas.

Both before the Algiers Accord and since, there have been localised conflicts and a continuing war of words between these northern factions, with both the CMA and the Platform directing verbal fire at the government, criticising its slow progress in addressing the north’s political and economic exclusion and the stalled “Demobilisation, Disarmament, and Reintegration” process.

Much will ultimately hinge on the tactics adopted by these rival blocs, but Mali watchers are also concerned by two developing trends: the growing reach and changing tactics of jihadist groups, and the unrest erupting in previously peaceful central regions.

In the central regions of Mopti and Ségou, small-scale skirmishes are beginning to hint at a potentially bigger problem. They may not be directly related to the larger conflict in the north, but the humanitarian consequences could be significant and they certainly contribute to Mali’s ongoing instability.

Absent from the general peace process appears to be any real representation from the central region of Mopti, the focus being much more on the northern regions of Kidal, Gao, and Timbuktu. This also means that the concerns of Peul communities, both pastoralists and sedentary farmers, have not yet been addressed. Peul activists complain of continuing and wholesale human rights abuses by both government and Tuareg rebel forces. The attack on 19th July against a well defended Mali Army base will highlight the emergence of this group and its claims that it represents the interests of the Peul ethnic community.

The National Alliance for the Safeguarding of the Peul Identity and the Restoration of Justice (ANSIPRJ) only announced its emergence as a military force in early July 2016. Its leader is Omar al-Janah, a 27-year-old former teacher, reportedly of Tuareg and Peul parents. Al-Janah claims that he has 700 fighters at his disposal, though he claims he is neither a separatist nor a jihadist.

A second group has emerged in the central region: the Macina Liberation Front, which takes its inspiration from the Macina Empire of the 19th century, is led by the radical preacher Amadou Koufa and appears to be aligned to Ansar Dine.

It appears that growing violence in the region may be rooted more in traditional land disputes and the aftermath of the rebellion of 2012.

Peul leaders are being punished for an alliance they formed with the nominally faith-driven Movement for Oneness and Jihad in West Africa (better known as MUJAO), once the dominant power in Gao, an alliance not fundamentally one of shared ideological conviction, but forged out of a joint hostility towards the MNLA and the Malian authorities.

Human Rights Watch claims that the state’s reassertion of control in the central region has been clumsy and alienating, with reports of frequent excesses by government troops and mishandled mass arrests, reinforcing local antagonism against the authorities in Bamako, strengthening Peul resentment and enhancing the chances of retaliatory violence.

With the UN peacekeeping mission of 11,000 men already overstretched in the north and continuing to suffer casualties, there is understandable fear in Mali of a disintegrating centre. The UN has noted the recent arrival of displaced people fleeing violence between Peul and Bambara communities in central Mali. It has blamed much of it on banditry, while accepting that the patterns of violence are changing and that the central region poses an alarming set of new challenges.

Jihadist insurgents were not part of the peace deal, in fact the agreement sought to isolate them, but they have been far from neutralised.

UN reports on the progress of its Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission (MINUSMA) are studded with details of attacks on its camps and of UN vehicles being hit by IEDs. Some 90 UN peacekeepers have lost their lives in Mali, in what is by far the deadliest peacekeeping mission in the world at the moment.

The French Operation Barkhane, run in collaboration with Chad and Mali, has also had its casualties during counter-insurgency operations in the far north.

Rather than just being pinned down in the north, or departing en masse for Libya, jihadist fighters have increased their striking radius within the country’s borders. The November 2015 attack on Bamako’s Radisson Blu Hotel showed their capacity to strike a high-profile target in the capital.

But the true extent of any jihadist threat remains far from clear. The level of support, chain of command, and alliances of groups like al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) are the subject of constant speculation. Algerian-born Mokhtar Belmokhtar, the most notorious extremist leader in the region, has been well entrenched in northern Mali for years.

Some, but not all of the violence, can be attributed to jihadist groups. The UN acknowledges there is more than one enemy. The chair of the UN’s Security Council Working Group on Peacekeeping Operations wrote in December 2015 that the “blurred lines between terrorist and criminal groups make it difficult to determine if the threats directed towards MINUSMA are ideologically or criminally motivated.”

The most recent report on Mali to the UN Security Council from UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-Moon (delivered on 31 May) recommended more than 2,000 new troops for MINUSMA. However, from a military perspective, simply deploying more UN troops to strong points in Gao and Kidal, unable even to address security problems just a few kilometres out of town, would appear to be a waste of military assets.

The Algiers Accord acknowledges the economic renewal of the north, which has suffered years of deprivation and neglect, as a fundamental issue towards achieving a peaceful solution to Mali’s internal security problems.

The Accord also outlines an innovative decentralisation programme, stopping short of regional autonomy. One of the major hurdles has been establishing two new administrative regions (as agreed on in Algiers), the first being in Taoudéni in the northwest (north of Timbuktu), with the other in Ménaka, in the northeast, and appointing new governors.

Humanitarian access for relief agencies is also seen as an essential element in the peace process, but remains gravely compromised by security problems and the lack of a state military presence in many areas.

Certainly a greater sense of urgency is needed from the Malian government on these key issues if it is to win the confidence of its Algiers co-signatories.

Leave a Reply