Islamic State (IS) encroachment, and the risk to the region

Islamic State (IS) encroachment, and the risk to the region

What had been common knowledge for some time within national security organisations in Australia and SE Asia became clear to the world this month with Islamic State’s efforts at creating a caliphate in The Philippines

On 23rd May, in the southern Filipino island of Mindanao, in Marawi, a predominantly Muslim town of 200,000 inhabitants, deadly clashes erupted between The Philippines military and initially around 100 Islamist militants from the violent Maute group, aligned with the Abu Sayyaf terrorist group, leading the central Government to declare martial law across the province.

The fighting in Marawi erupted after Filipino soldiers raided a house where they believed senior Abu Sayyaf militant Isnilon Hapilon was in hiding. The raid led to the emergence from ambush of scores of Maute militants keen to take on the military who, outnumbered, retreated from the town, leaving the militants to rampage under the banners of the black IS flags, where they raided two jails, freeing more than 100 inmates, most of whom subsequently joined them in the fighting.

The former leader of the Abu Sayyaf Islamist terror group, Isnilon Hapilon, is now reportedly an Islamic State chief, having changed his name to Abu Abdullah al-Filipini in 2015 and pledging his allegiance to Islamic State. In early 2016, IS announced his appointment as “Emir” of the new “Philippines Province”

The former leader of the Abu Sayyaf Islamist terror group, Isnilon Hapilon, is now reportedly an Islamic State chief, having changed his name to Abu Abdullah al-Filipini in 2015 and pledging his allegiance to Islamic State. In early 2016, IS announced his appointment as “Emir” of the new “Philippines Province”

An Arabic-speaking preacher with an engineering degree from the Philippines’ top university, he is now one of the world’s most wanted terrorists. Hundreds of people have died and millions of dollars have been spent in the hunt for the Abu Sayyaf chieftain, but he remains elusive. He is known to have moved out of the Abu Sayyaf stronghold of Sulu Province in 2016 to bring other Islamist groups in the southern Philippines under the IS banner. The United States considers Hapilon a major international terrorist and have a bounty of US$5 million for his capture.

An Arabic-speaking preacher with an engineering degree from the Philippines’ top university, he is now one of the world’s most wanted terrorists. Hundreds of people have died and millions of dollars have been spent in the hunt for the Abu Sayyaf chieftain, but he remains elusive. He is known to have moved out of the Abu Sayyaf stronghold of Sulu Province in 2016 to bring other Islamist groups in the southern Philippines under the IS banner. The United States considers Hapilon a major international terrorist and have a bounty of US$5 million for his capture.

Since the attack in Marawi, information has emerged that the predominantly Muslim city had been selected to be the centre of Islamic State’s regional SE Asia base. The Philippines Army Chief of staff, General Eduardo Ano, confirmed that evidence has since been uncovered in Marawi that clearly demonstrated the intention of not only an act of rebellion, but the dismemberment of a portion of the Philippine territory through the occupation of the whole of Marawi city and the establishment of an Islamic State and Government.

Many of the militants in Marawi are locals from the region. The ill-equipped Philippines military has in the past mostly operated against Islamist rebels in mountainous territory or on remote islands, and is unused to urban warfare and lacks training in urban terrain tactics. To aid the militants further is the history of Mindanao’s clan warfare (known locally in dialect as “rido”) where most residences and building have basements and are built with thick concrete walls, fortress-like, making it difficult for attackers to breech the defences.

Many of the militants in Marawi are locals from the region. The ill-equipped Philippines military has in the past mostly operated against Islamist rebels in mountainous territory or on remote islands, and is unused to urban warfare and lacks training in urban terrain tactics. To aid the militants further is the history of Mindanao’s clan warfare (known locally in dialect as “rido”) where most residences and building have basements and are built with thick concrete walls, fortress-like, making it difficult for attackers to breech the defences.

Since the outbreak of the violence in Marawi, hundreds of people have been killed, including foreign Islamic State fighters from Indonesia, Singapore, Malaysia, Morocco, Chechnya, Saudi Arabia and Yemen, leading the Australian Minister of Foreign Affairs to warn that the southern Philippines risked becoming the foundations of an Islamic State caliphate, with many battled-hardened Islamic State fighters fleeing the Middle East to establish training camps in the restive southern Province.

Since the outbreak of the violence in Marawi, hundreds of people have been killed, including foreign Islamic State fighters from Indonesia, Singapore, Malaysia, Morocco, Chechnya, Saudi Arabia and Yemen, leading the Australian Minister of Foreign Affairs to warn that the southern Philippines risked becoming the foundations of an Islamic State caliphate, with many battled-hardened Islamic State fighters fleeing the Middle East to establish training camps in the restive southern Province.

A measure of the concern at the current state of events has been demonstrated by the deployment of US Special Forces to assist the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) in ending the siege of the southern town, though the US Government has stated that US forces are providing technical support only, including aerial observation and reconnaissance drones, but are not engaged in combat missions themselves.

The US Embassy in Manila announced that US Special Operations Forces are providing help to Filipino troops battling Maute and Abu Sayyaf militants. In a statement, the Embassy said that “The United States is a proud ally of The Philippines and we will continue to work with the Philippines to address shared threats to the peace and security of our countries, including on counterterrorism issues”.

Most of the 200,000 inhabitants fled the city after the Islamic State aligned militants started executing non-Muslim civilians in the town and it is estimated that as many as 40 foreigners are fighting alongside the Philippine militants, most of them from Indonesia and Malaysia, though some have arrived from the Middle East.

The seizure of Marawi has alarmed South-East Asian nations which fear that Islamic State is attempting to establish a stronghold on the Philippine island that could threaten the whole region, as ISIS is slowly but relentlessly forced from Syria and Iraq by the fierce international coalition campaign.

On 1st of June, in a friendly fire incident by air force gunships, the Philippines military suffered the loss of 10 troops, and then later that week a further 13 Philippine marines were killed in battle, while a further 40 were wounded, in another setback in the government’s quest to retake the city. Reports are that the marines were conducting clearing operation and died during intense house-to-house fighting during which time they encountered improvised explosive devices (IEDs – a favoured tactic of IS in the Middle East) and were also attacked by rocket-propelled grenades (RPGs).

The militants continue to put up fierce resistance despite facing an Army Brigade supported by armoured vehicles and helicopter gunships. The most recent deaths take the number of security force members killed to date to over 60, with 30 civilians and more than 200 rebel fighters also killed, though these are only estimates of militant losses. Military progress has been hampered by the need to avoid causing civilian loss of life and the destruction of mosques where many militants had taken up positions.

President Duterte recently replaced the general leading the initial offensive, and gave assurances to the country that the uprising would be suppressed quickly, but so far the militants continue to put up fierce resistance, defying Duterte’s optimistic and brash assertions, running the risk for Duterte of damaging his hard man image.

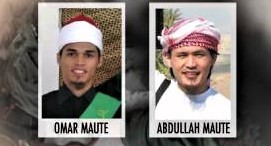

A senior Philippines Army spokesman claimed that the 2 best known of the 7 Maute brothers, the leaders in the Islamist militant group, had been killed. All 7 of the Maute brothers are believed to be inside Marawi, while their mother, father and one cousin, Mohammed Naiom Maute, believed to be the group’s primary bomb maker, have been arrested in Cagayan de Oro, about 100kms from Marawi, as they attempted to flee the battlefield.

The Maute Group is based in Lanao del Sur in Mindanao province and is considered tactically adept and comfortable with the use of social media to widely propagate their ideology. Named after the two Maute brothers who studied the conservative Wahabi ideology while working in the Middle East, the group represents a new form of Islamist extremism in The Philippines, driven by the conservative ideology. Its membership is considered to be substantially more sophisticated than other pro-IS movements in the region.

Omar-Khayam Maute studied at the world-renowned Al-Azhar University in Cairo, while his brother Abdullah studied Islamic theology in Jordan. Omar-Khayam married the daughter of a conservative Indonesian Islamic cleric and returned with her and their 5 children to Mindanao to pursue his career as an Islamic teacher

The group first came to the notice of The Philippines security authorities in 2013 when it claimed the bombing of a street market in Davao City, the hometown of President Duterte, in which 15 people were killed. A foiled attack in Manila in November 2016, near the United States Embassy, confirmed concerns that the group had established operational cells outside of Mindanao.

The group first came to the notice of The Philippines security authorities in 2013 when it claimed the bombing of a street market in Davao City, the hometown of President Duterte, in which 15 people were killed. A foiled attack in Manila in November 2016, near the United States Embassy, confirmed concerns that the group had established operational cells outside of Mindanao.

Earlier this year, in April, Filipino troops seized what they announced to be a major Maute camp, replete with bunkers and trenches, and declared that with the capture of this base, the threat from the group had diminished. Clearly however, their optimistic outlook was premature, and it is becoming more evident that the Maute Group and the Sabu Sayaf group appear to be consolidating their military ties.

The scale and sheer ambition of the Maute combatants in Marawi, the presence of a large number of trained and motivated foreigners, and the ruthlessness and tenacity shown by the militants as they resist several thousand Filipino soldiers, mark this event out from earlier militant actions. Chatter being monitored on jihadist websites and forums across SE Asia appears to be gathering enthusiasm.

The upsurge in ISIS-related activity in the southern Philippines has heightened concerns that the region could soon become a de facto “wilayat,” or province of the “Islamic State.

A wilayat in the Philippines could provide sanctuary for Southeast Asian militants returning from the Middle East conflict zones, or for those who failed to make it there in the first place, and who would find the region a convenient and hospitable transit point from which to return home, providing not just sanctuary, but an opportunity to regroup, establish connections, build their regional networks, train and plan operations.

With the growth of militancy in The Philippines, SE Asian tourist destinations popular with Australians and other Westerners could now be under threat as jihadis look to create a new stronghold in SE Asia. The region is already home to violent fanatics who share the IS interpretation of Islam and its determination to destroy its enemies. Dangerous terror groups already operate in Indonesia, Thailand, Myanmar, and Malaysia, and regional defence and security authorities believe that the IS objective is to consolidate these various groups, with the strategy of creating a powerful regional jihadist movement.

Deadly bomb attacks on the popular Thai tourist destinations of Phuket and Hua Hin in June 2017 have been blamed on Muslim separatists leading an insurgency in the south of the country, along the border with Malaysia. It is known that hundreds of Islamic extremists from Southeast Asia travelled to Syria and Iraq to become ISIS fighters and are now attempting to return home with funding, combat skills, social media skills and access to terrorist networks.

A unit in Syria called Katibah Nusantara (established in September 2014), led by Indonesian militants, claims to represent Southeast Asians (principally Indonesians and Malaysians) fighting for IS, and reportedly has around 200 fighters based in the city of Raqqa, now under attack by a coalition of Western supported militias. KN members spread propaganda, recruit new fighters and co-ordinate attacks, and are understood to be in contact with likeminded organisations in their homelands. Considering Indonesia has the largest Muslim population in the world, it is only natural for ISIS to look to the region for its next stronghold.

IN INDONESIA, police arrested a man on suspicion of helping Indon¬esians join the Filipino and foreign Islamic militants who overran Marawi, and two others who ¬allegedly helped inspire a double suicide bombing in Jakarta on 24th May that killed 3 policemen and the 2 suicide bombers.

A police spokesman said that Police had ¬arrested a suspect in Yogyakarta, in central Java, and charged him with ¬facilitating Indonesians to travel to Mindanao, where they joined the ¬Islamic State-affiliated milit¬ants who continue to occupy parts of Marawi more than three weeks after their initial attack.

A police spokesman said that Police had ¬arrested a suspect in Yogyakarta, in central Java, and charged him with ¬facilitating Indonesians to travel to Mindanao, where they joined the ¬Islamic State-affiliated milit¬ants who continue to occupy parts of Marawi more than three weeks after their initial attack.

Indonesian authorities blamed the Islamic State-affiliated Indonesian group Jemaah Anshar-ud-Daulah (JAD), a group known to have sourced weapons from Mindanao, for the dual suicide bomb attack in Jakarta that killed the three police officers, the latest in a series of low-level attacks in Indonesia by Islamist militants in the past 17 months.

Indonesia’s National Counter-Terrorism Agency, BNPT (Indonesian: Badan Nasional Penanggulangan Terrorisme) confirmed this week that at least 7 Indonesians fighting with the Maute and Abu Sayyaf groups in Marawi are JAD members. So far, the attackers’ lack of experience has limited the scale and impact of their actions, but a battleground on Indonesia’s northern doorstep would provide an opportunity for the new generation of jihadists to build contacts and skills.

Mindanao has been a training ground for some of the most recognisable names of Southeast Asian jihadism. It is where Indo¬nesia’s Jemaah Islamiyah militants honed their skills, including the three Bali bombers.

Although the traditional sea routes have been exploited for years by Malaysian and Indonesian militants moving to and from southern Philippines, many jihadists over recent years have been able to fly undetected on commercial flights into Mindanao, and many Indonesian jihadis-in-waiting have been reinvigorated by recent events in Marawi and the difficulty the Philippines military have encountered in clearing the militants from the city.

Iqbal Hussaini, a reformed Indonesian gun runner also known as Ramli, who spent a year training in Mindanao jihad camps and who has served time in Indonesian jails for smuggling weapons from southern Philippines to terrorists involved in the 2002 Bali bombing and 2004 Australian embassy bombing in Jakarta, claims “I know a lot of Indonesians who are thinking about joining the Maute group in Marawi. Many are looking for the next jihad. The likelihood that Marawi will become a base for ISIS is very high.”

He further claimed that there are still Indonesians fighting in Mindanao with more-established groups such as the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) and Abu Sayyaf, who would likely act as contacts for those who may be drawn to joining the Maute group.

Such a scenario is exercising the minds of Southeast Asian and Australian security, intelligence and defence authorities, who are contemplating the possibility that Mindanao could become a haven for battle-hardened foreign fighters from the Middle East, training the next generation of green “wannabe” jihadists from the region.

This potential for the Marawi siege to breathe new life into Islamist insurgencies and trigger fresh terror attacks across the region featured prominently in discussions during Singapore’s annual Shangri-La defence dialogue (2-4 June 2017), and in subsequent bi-lateral defence talks between Australia and the US. Singapore’s Defence Minister warned those attending the conference that should the situation in Marawi escalate “it would pose decades of problems for ASEAN cities……(and could) prove a pulling ground for would-be jihadists who can launch attacks from there.”

Indonesia’s young democracy is under pressure from Islamic extremists whose pulling power was underestimated before the demonstrations of late 2016 and early 2017 against ethnic-Chinese Christian governor, Basuki Tjahaja “Ahok” Purnama. One Jakarta rally drew 500,000 people, protesting against the Governor, and shocking the Government.

Understanding the threat at last, the Indonesian Government is now fighting back, recently announcing that it would seek court approval to ban the ultraconservative Islamist group Hizb ut-Tahrir Indonesia (HTI) for posing a threat to national unity. The HTI, part of an inter¬national organisation banned in many countries, wants an Islamic caliphate to replace the Indo¬nesian government.

Understanding the threat at last, the Indonesian Government is now fighting back, recently announcing that it would seek court approval to ban the ultraconservative Islamist group Hizb ut-Tahrir Indonesia (HTI) for posing a threat to national unity. The HTI, part of an inter¬national organisation banned in many countries, wants an Islamic caliphate to replace the Indo¬nesian government.

Felix Siauw, a popular Hizb ut-Tahrir preacher, and a key recruiter for HTI on Indonesian campuses, says the government is “trying to weaken Islam and Islamic groups. There are big changes going on in Indonesia……the government was made to see for the first time that there is an emerging Muslim force outside of the conventional Muslim organisations which they were able to control” (referring to Nadhlatul Ulama and Muhammadiyah, Indonesia’s two largest Muslim organisations). “They’re trying to contain and delegitimise this new force by labelling them radicals, anti-¬diversity and also by trying to criminalise some of its leaders. Muslims are rising up, Muslims are becoming more aware of their Islamic duty, of the importance of implementing sharia law”.

Fortunately, this view is not reflected by the large majority of Indonesian Muslims, most of whom still practice a tolerant strain of the religion

Leave a Reply